Islamic Space & Time Reflected in Architecture

This is a condensed explanation of reading from A Sense of Unity (Ardarlan) and Islamic Design in West Africa (Prussin)

Tradition, the pervasive idea that animates people, inspires man’s creative energies and brings him to a sense of totality. A Hermetic concept, sacred geometry and polarized light all reflect aspects of these totalities within the universe: man as the microcosm of the universal macrocosm. Knowing the esoteric thought that underpins creativity facilitates a deeper actualization of one’s imagination.

Architecture is the interface between art and science, formally in geometric harmony and metaphorically in externalization of form. Form is actualized matter; it is a metaphysical duty for an architect to cultivate the form of their work to spiritual sophistication. Science is guided by laws (conservation and logic that underpins physics and math), yet many are unaware that art also has guiding principles.

“The Law is the circumference, the Way is the radii leading to the center, and the center is the Truth.” —Nader Ardarlan

In Islamic cultures, a particularly beautiful manifestations of this arise in places of worship, where one can experience a sense of unity with the universe internally and externally. Middle Eastern languages have two connotations of the word m3na that enables judgement: “meaning” literally and “spiritual” metaphorically. These inform the distinction between shari’ah, the path man walks, and tariqah, the street he walks on.

Shari’ah is now known as Islamic law, and tariqah is analogous to the Taoist “way.” Both lead to Islamic truth, haqeeqa, i.e. a sense of unity with God. Shari’ah is omnipresent in Islamic day to day life, but tawhid is subtle and guided the creative and intellectual principles behind Islamic intellectual thought at its peak.

Those divinely inspired create beauty to lead man to greater spiritual awareness to unity. The central postulate of the Islamic “way” is that every form has an externalized form and an internalized essence (nuanced from an animist interpretation). Form, the container of this essence, is created with objective beauty. Man’s spiritual awareness is the bridge that gifts this essence of spiritual beauty to a routine world.

For example, man is the container of awareness and spirit. He is built through objective laws from a cell into a matured and complex animal. However, a man can grow into a fully-functional adult and not be self-aware. The development of the intellect and of reason come from the exercise of cognitive challenge as dubbed by spiritual laws. Not all men are of the same spiritual level much like how not all men are of the same intellectual level. Spiritual law was the subject of contemplation for many Sufis who hoped to eloquently define them. In Europe, they defined man by the boundary of skin and clothes (sensory boundaries), but Sufis define man by the essence within (spiritual boundaries).

“Proportion is to space what rhythm is to time and harmony to sound.” — Nader Ardarlan, referencing Rumi.

Space’s intimate relationship with time means it is also a reflection of changing perception of time. As the “locus” of spirit, space is defined in reference to the sky and heavens, which gives it a system analogous to the six degrees of freedom. The mind first seeks cosmic order, then regional order, and finally local order. Quantitative space follows from qualitative space. The space is a positive aspect that generates form that shape decorates and not vice-versa. For Ardalan, a city is bounded by the positive space that carves a flow between buildings, and negative space as the carved out, ordered buildings. Active space is time in motion, and passive space is manifested in form produced by movement.

Note: Ardalan references a beautiful analogy to one of Rumi’s poems to show the similarity of articulation between music and architecture, both air and space in motion, that you should give a read.

Shape arises from bounding a section of space. The beauty in geometry comes from the harmony of “personality” reflected in numbers, which are in turn a reflection of unity (see Flatland). The beauty we arrive at is both an objective and subjective beauty. Order and proportion were not drawn arbitrarily as rules from man; they are intrinsic to the universe. Much like how the platonic solids had elemental meaning as they could be inscribed in a sphere, sacred geometry ascribes implication to each shape. Islamic cultures extend them into repeating patterns using the golden ratio as their tool of proportion (Fibonacci ripped off the Arabs…) to be in harmony with nature.

Visual representation of consecutive dimensions.

In Middle Eastern society, architects are granted the title of muahandis — “he who gemetricizes.” Architects were educated concurrently in mathematics and in spiritual law, and the final center of learning was the spiritual school, not the artisan college. This acquisition of mathematical-spiritual frameworks facilitated the intricacies of divine expression within their work. Ardarlan relates architectural excellence to “strength of the encounter and clarity of its expression.”

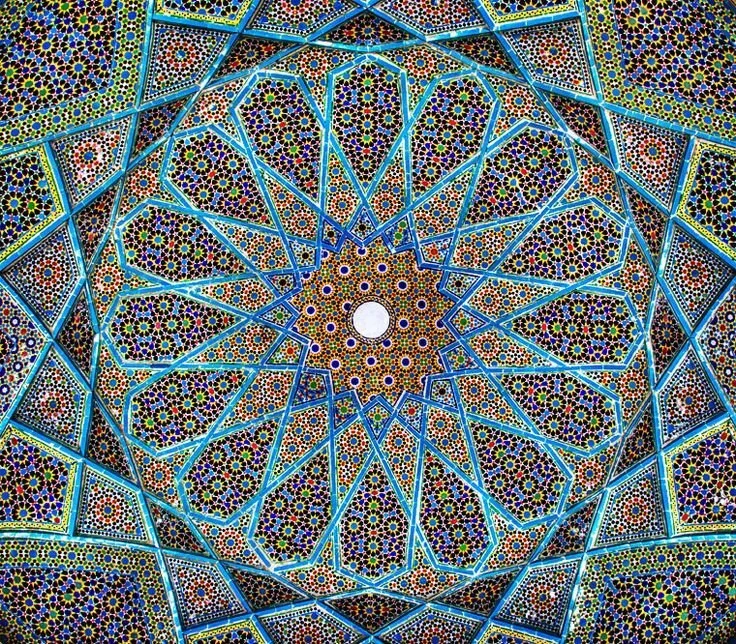

Islam does not put individuals on a pedestal (Muslims are not allowed to depict Muhammed in images, only use him as a reference for an enlightened man). Instead, geometry, unity and proportion are were used in worship for the infinite nature of Unity through tiling form and pattern. Sufis used Hermetic and Pythagorean geometry and Vitruvian proportion to create tilings of sacred geometry that are ubiquitous in their architecture now. The circle represents unity and cycles of nature. The triangle is the first form to bound space and represents the soul. The stability of four forms the square. Architects aim to immerse the viewer with resonant geometry.

Ceiling design of a mosque representing Sufi geometry. (Above)